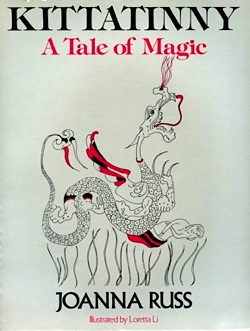

Immediately following The Two of Them—within the same year, in fact—is Kittatinny: A Tale of Magic (1978). Kittatinny is a middle-grade book written by Joanna Russ for Daughters Publishing, with illustrations by Loretta Li. It’s out of print and mildly difficult to find. The story follows young Kit through a series of trials and adventures as she comes of age and comes home, finally, to find something worth leaving for. It was written out of an express desire to offer young women the same kind of self-transformative narrative of adventure so common to young men, without having anything to do with housework or husbands.

Kittatinny is an odd duck, considered in the continuity of Russ’s other works, especially following the nigh-on meltdown of The Two of Them. For one thing: it’s positive and it has a happy ending. There are moments of fear and moments of sorrow, but overall, it’s a pleasant book with plenty of heft. It reminds me, in a strange circular way, of Neil Gaiman’s The Graveyard Book: it has a story made for young readers, but it has moral and thematic implications for adults. The book was a joy to read—undemanding, compared to Russ’s other work—though it still expects quite a bit from the reader in terms of feminist analysis and understanding of women’s sexuality.

It’s a frank, open-handed book. Throughout the narrative, which is told through a streamlined, sleeker and only slightly easier version of her usual prose, the honesty of the narrator—Russ—is refreshing, her voice candid and gentle. (I did say it was an odd duck, didn’t I?) This pleasantness, this richness, makes for a fabulously touching reading experience; I found myself responding intensely to simple scenes, like the Warrior Woman calling all of the other warrior women throughout history to fight the fire in the wood. The huge spectrum of powerful women all come to one place—white, black, brown, old, young, all types—to fight together, as Kit watches and is awed by their presence It’s difficult not to have an emotional response, at least for me.

Kittatinny is a book about adventure and self-discovery, but it’s also a book about girls discovering the history of women and the potential of women—it’s an attempt to stop the erosion of feminist history, in a subtle way. There are only a few male characters in the story, all of which are either mentioned in name-only or are shown briefly, like the Miller’s son. (I except B.B., who begins the story as a boy baby and slowly evolves as an Idea over the course of the text to be another version of Kit herself, trapped in the mirror, a reflected version of who she is inside or wants to be—someone who can yell and pitch a fit and fight. Kit herself can only see him as male for most of the story because she can’t reconcile a girl being allowed or able to behave as B.B. can; by the end, however, this seems to change.)

The ending is an excellent culmination of the adventures that come before—Taliesin, the mother of all dragons and all the world, the shade of Briar Rose who has become a monster by being locked away in “safety” by her parents for all time, wolves and living rocks. It all comes together in one of Russ’s sideways-sliding endings that knocks everything on its head and plays with a postmodern sensibility. The book is aimed at an age group of 12-13ish, but I think it’s not too difficult—she manages to make the shift fairly transparent, even as she suddenly throws everything into a new perspective. When Kit returns home an adult, sees the herself/B.B.’s ghost in the mirror, and kisses both the man who wants to marry her and the young woman who has become her best friend, Rose, the reality of her adventures becomes lighter: she remembers both things, growing up in the valley and befriending Rose (who has had “dreams” about Kit’s adventures also, matching hers, plus some new ones) as well as taking her long journey. So, did it really happen? Did she and Rose imagine these things together, or did she really have a magic adventure—but, the real point at the end is not about the questionable reality of the adventure. It’s that in her mind, it was real, and her development as a person that allows her to make her final choices in the book was also real.

That ending is lovely, by the way, though I wonder how it was received by audiences in 1978—hell, I wonder how parents would respond today, considering the uproar about LGBT young adult novels that pops up from time to time. This is a young reader’s book that’s frank about sex—after all, Kit is from a farm; she knows what sex is, and the book retains a healthy understanding of bodies and feelings, which is doubly awesome, because young teens have sensual feelings and also need positive images of sexuality. The interesting bit is that in the end, the lead character is revealed to be at the very least bisexual if not a lesbian. She may kiss the Miller’s son and feel a spark, but after he leaves, having asked to marry her and been rebuffed, Rose comes in, and she’s well-dressed because she’s being married off to a rich merchant. They sit together, and talk about the adventures, and finally kiss—which Kit finds even more wonderful.

At the very end, as Kit walks out of town, she sees someone else in trousers coming up to her And it’s Rose. That’s the close of the book. The young women run away to be together, romantically and in friendship. It’s an ending I find fabulous and moving—there aren’t enough books for young queer women, there really aren’t—as well as surprisingly positive for a Russ novel. It’s a happy ending, where the love of women for women triumphs. I almost wanted to weep, after watching Kit’s growth and development as a young woman with a woman-centered adventure, a burgeoning understanding of feminism and her own identity, that results in her leaving with her friend and might-be-soon lover.

I honestly wish this book was still in print; I’d happily give it to young women of my acquaintance, straight or queer. The view of the world in Kittatinny: A Tale of Magic is one where, despite the challenges of limitations placed on young women—you can’t be a Miller because you’re a girl, etc.—those same young women can break free of it and find individual identities. It’s pretty fabulous, and provides a breather in Russ’s oeuvre between relentlessly painful books. It shows that there is hope, in a way that The Two of Them didn’t, though it made an effort in the last pages. There is a future for feminism, for women, and for freedom—at least if there are books like this, and young women like Kit and Rose.

This is her only children’s book, and her second-to-last novel, but I think it did exactly what she wanted it to do: provide a story of development and adventure that is about young women, for young women, to give them something outside the realm of boy’s stories about boys or marriage tales. As B.B. tells Kit and Kit repeats to herself, “You’ve been hearing too many stories with wedding dresses in them.”

The next book is Russ’s final novel, a mainstream lesbian book called On Strike Against God. It’s a return to Russ’s more common form and tone.

Lee Mandelo is a multi-fandom geek with a special love for comics and queer literature. She can be found on Twitter and Livejournal.